Our first year in the Arkansas Canoe Club has been a good one. We’ve been impressed with their emphasis on teaching and on safety. They organize two big ‘schools’ every year – the whitewater school and the recreational paddling school (which we attended last year). Less highly publicized are tons of training opportunities for the people who teach at those events, and for others in the club. There are workshops and certification for kayak teachers, and canoe instructors. There are rescue classes at different levels.

This culture of knowledge and safety is something we’ve really benefited from. Our family wouldn’t have had the good start we did without those educational opportunities. We’ve felt pretty safe pushing ourselves a little bit, knowing that the people around us are well trained will be able to fish us out of the water if we need help. We think it’s very, very cool to be part of something that feels so committed to keeping people safe.

This spring, we had a chance to take a CPR/AED course from UAMS, without charge to us – the classes were sponsored by the canoe club. Now all three of us are certified CPR people. We have cards and everything. And we feel a lot more confident about actually providing help to someone in distress, instead of just standing nearby and looking concerned.

For several years, we’ve been thinking that we’d like to take a Wilderness First Aid class. We’re in the woods enough, with enough other people, that at some point, something bad is bound to happen. But since the WFA courses are expensive, we’d thought we should just send one person from our family, and we could never decide which one to send, so we never quite got around to sending anybody. But this spring, through the ACC, we were offered a WFA course for paddlers at a fairly reasonable price, so we wrote the check for all three of us to go.

In town or in the ‘frontcountry’, first aid is pretty straightforward – if there’s an emergency, you can generally count on help to come quickly. In the ‘backcountry’, even on a straightforward backpacking trip or an afternoon paddle, it’s important to treat things differently because trained professional assistance can be hours or even days away.

This is an idea we got comfortable with when we were caving a lot. If someone’s hurt, it takes awhile for a caver (or hiker, or paddler) to get out far enough to call for help. After that, it takes awhile – sometimes a long while – for medical help to get organized and make it to the injured person.

Because of this, the WFA class covers a lot more than a ‘regular’ first aid course. First, we learned first how to be sure we approach an injured person in the right way, trying to understand what happened and provide help without compromising our own safety. We learned to expand on the usual “ABC”s (Airway, Breathing, and Circulation) to D (Deformity) and E (Environment.) In other words, not only is it really important to be sure our injured friend is breathing and pumping blood, we also need to stabilize broken things and be sure that he’s kept warm, dry, and as comfortable as possible. We learned about ‘Head to Toe Checks’ and about other things to talk with the hurt person about. (Signs and symptoms! Allergies! Medications! Past medical history! Last intake/output! Events leading up to the injury!) There’s a lot to learn.

In the backcountry, it’s not enough to just stop bleeding – wounds may need to be cleaned, held closed, even re-cleaned and re-bandaged over and over to stop infection. We learned how to clean open wounds really thoroughly by practicing on cut-up oranges. We learned how to bandage appropriately, and even how to make bandages from clothes if needed.

In the backcountry, it’s not enough just to hold a broken bone still until help arrives – we learned how to make splints from available materials, how to move a person who might have spinal damage, how to make a stretcher from sticks and life jackets and pieces of rope. We learned how to reduce a dislocated shoulder with a jacket and a heavy bag. We learned how to monitor extremities for circulation and sensation and motion after bandaging.

Dislocations. Burns. HyPOthermia. HyPERthermia. Snakes. Diabetic emergencies. Eye injury. Seizures. Heart attacks. Spiders. It was all in the book. It was all on the whiteboard.

We also learned how to identify and treat shock. (Did you know that there are five different kinds of shock? Yep.) Our instructors were really practical about this stuff. For example, they taught us that, since we’re all pretty much always dehydrated when in the backcountry, we should just assume that all badly injured people are in shock. What that means to us in trying to help them is really that we should be aware of possible problems, keep them warm and be sure they drink enough. In addition to learning a lot about how to help others, we learned a lot about how to reduce our own chances of having something ugly happen to us while paddling or hiking.

Our friends Heather and Chris were in the class with us, along with several other people we don’t know as well. The neighbor dog attended the class on Saturday, but couldn’t get her certification because she missed Sunday’s session.

And we had a chance to practice, a lot, which was really helpful. We split into groups and pairs, and pretended to assist people who had fallen, or who had serious wounds or broken bones or head injury. Sometimes we used makeup to make the injuries seem more realistic, and sometimes we didn’t, but there was real benefit of going through the motions over and over.

Most of the time we were practicing on the dry grass in the sunshine outside the barn we used for class, but we had to practice at night, too. Late on Saturday evening, while we students were in the barn, one of the instructors ran in. He told us that there were injured people in the woods. We searched the area to find them and tried to identify their assortment of head wounds and broken legs and shoulder injuries and scrapes and bruises. We hauled one guy out from under a tree. We splinted broken things, bandaged wounds, all while monitoring vital signs, treating shock, and keeping them warm. We worked together to get them on improvised stretchers and carried up to the barn.

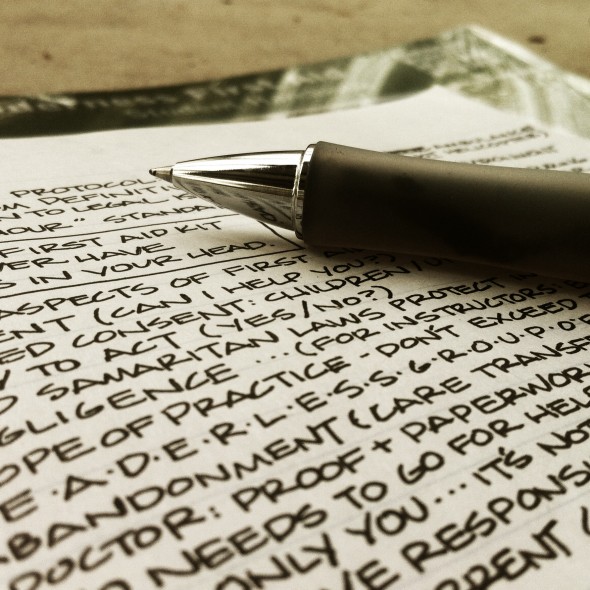

Over the next month or so, we’ll be working on building three good first aid kits. We’ve know we needed to carry something beyond the standard bandaids-and-ibuprofen baggie, and now we have a good list of small, practical items to keep in a pack. More important than what we carry with us, though, are the principles we learned from twenty hours of instruction and practice. One one page of my notes, I’ve written this: The best first aid kit you’ll ever have is in your head.”